Rocket Mechanics from Kerbal Space Program

- mollievonehr

- Mar 7, 2025

- 7 min read

by Michael Lingg

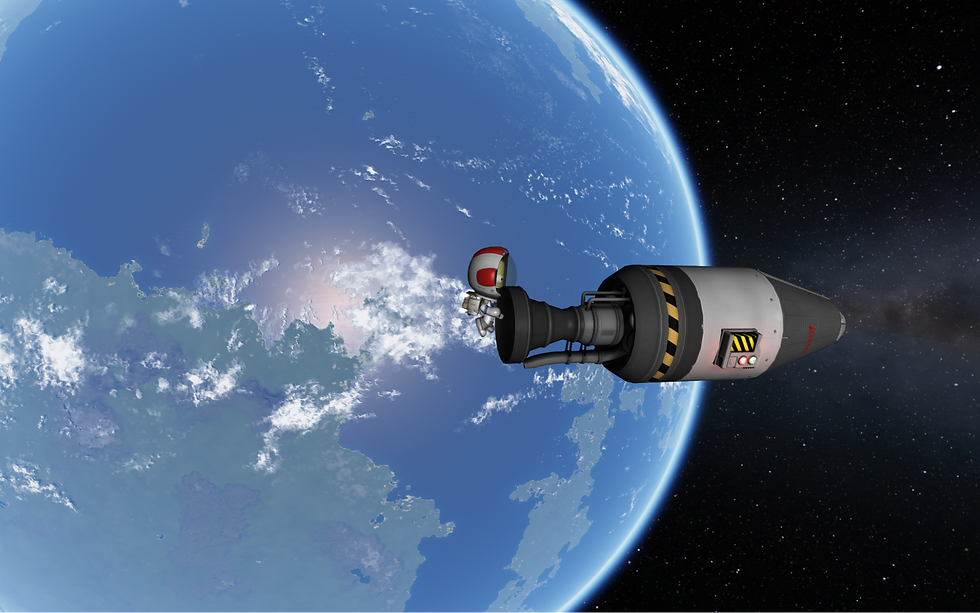

Understand how to maneuver in orbit before you launch your rocket, or you may find yourself pushing your rocket back home.

Orbital Maneuvers

Introduction

In the first article, we explored how to reach orbit from (theoretically) any celestial body. Now that we are in orbit, we will look at how maneuvering in orbit works. This article introduces basic orbital maneuvering but does not yet cover travelling between celestial bodies.

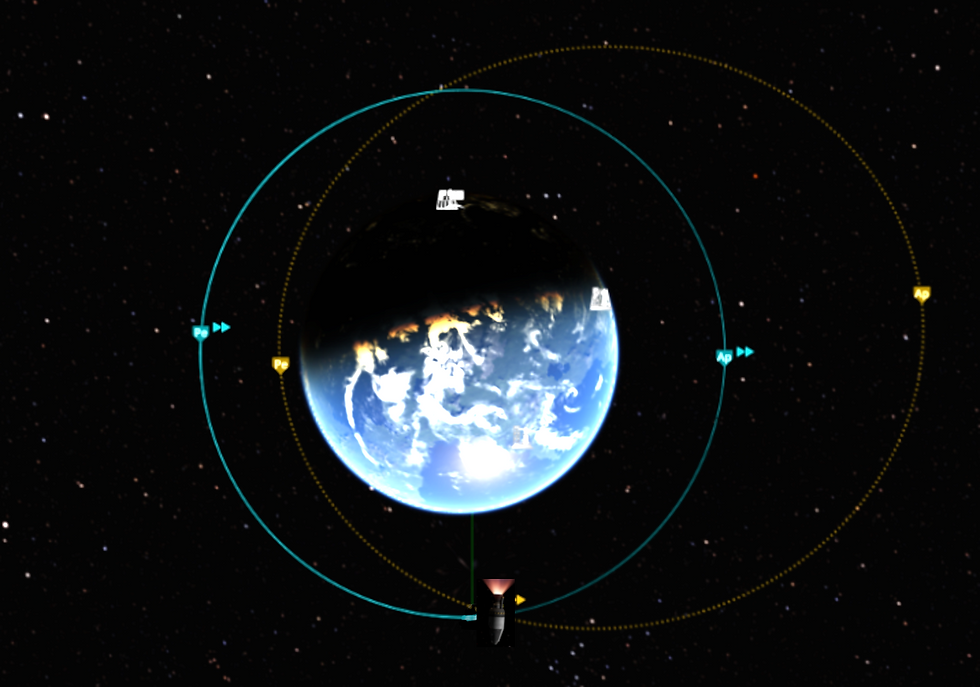

The image below depicts a rocket’s orbital path along with a maneuver node (highlighted inside of the orange box). The maneuver node in KSP allows players to plan maneuvers that add velocity to the orbit, at the location of the node, along each direction of the three axis relative to the orbit, or any combination of these three axes. The three axes are:

Along the direction of the orbital motion.

Perpendicular to the orbital plane

Toward/away from the center of the orbit.

Now we will break down how each maneuver axis works.

Maneuver along the direction of the orbit.

First we will look at accelerating the rocket along the direction of the orbit. The two directions we can accelerate are Prograde and Retrograde.

Prograde

A Prograde burn increases the spacecraft’s velocity along its current direction of travel. The image below shows a rocket that is orbiting Kerbin counterclockwise (eastward), depicted by the blue circle. The rocket is thrusting Prograde, which causes the opposite point in the orbit to increase altitude. In the image the opposite point of the current orbit (blue circle) is the periapsis (the lowest point in the orbit). The dashed yellow ellipse shows the final orbit, and illustrates how the former periapsis will increase in altitude and will become the apoapsis (the highest point in the orbit).

As a result of the previous maneuver, the rocket is in an elliptical orbit (a higher apoapsis than periapsis). If our rocket burns in the Prograde direction at the new apoapsis (Prograde at the apoapsis is 180 degrees from the previous Prograde burn as we have looped around the body we are orbiting) we will begin to raise the periapsis. Eventually the burn will bring the periapsis to the same altitude as the apoapsis, and the orbit of the rocket will be circular again. This technique is known as a Hohmann, or bi-impulse, transfer, where two rocket burns (or impulses, which is the measure of the exact energy added to the orbit by the complete burn) are needed to increase the radius of a circular orbit, while ensuring the final orbit is still circular. One burn raises one half of the orbit, producing an elliptical orbit, and a second burn, halfway around the orbit, raises the other half of the orbit to complete the circularization.

Retrograde

A Retrograde burn decreases the velocity along the orbital path, lowering the altitude of the opposite point of the orbit. A Retrograde Hohmann transfer can also be used to shrink a circular orbit.

Retrograde burns are often used to initiate atmospheric reentry, lowering the periapsis of the orbit such that the rocket reenters the atmosphere, and atmospheric drag will slow the rocket until it can land with parachutes, or on a runway like the space shuttle. The Mercury program used a Retrograde rocket package with three solid fuel rockets to bring the Mercury capsule to reentry: https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/rocket-motors-solid-fuel-Retrograde-mercury-19/nasm_A19680571002

Accelerating “North” and “South”.

Next is accelerating north and south relative to the orbit. The two directions we can accelerate are Normal, which if the orbit is the curled fingers of your right hand then Normal is your thumb, or Anti-Normal, the opposite direction. These maneuvers are used to produce inclination changes, or to adjust the plane of the orbit.

Normal

Burning in the Normal direction rotates the orbit around the axis that runs from the rocket through the center of mass the rocket is orbiting. This rotation will cause the next half of the orbit upward relative to the original orbital plane, and the previous half of the orbit downward. This maneuver can be used to transition from an equatorial orbit to a polar orbit, but is much more expensive than burning for a polar orbit immediately from liftoff. The primary use of this maneuver is matching the plane of another orbital body, such as how Pluto is 17 degrees off plane, or Minmus has a 6 degree orbital inclination. In the case of a flyby of such body, like the New Horizons mission, the rocket only needs to intersect with the target body at some point in space. If the rocket is attempting to match orbit with such a body, when it is not possible to launch directly into the correct inclination, this maneuver can be used to better match inclination with the target body, and lower the relative velocity as much as possible when intercepting the target.

Anti-Normal

The Anit-Normal maneuver is the opposite of the Normal maneuver. Maneuvering in the Anti-Normal direction will rotate the next half of the orbit downward relative to the original orbital plane, and the previous half of the orbit upward.

Accelerating toward or away from the body being orbited.

The final maneuver is accelerating toward or away from the body being orbited, or the gravitational center of our orbit. The two directions we can accelerate are Radial Out, away from the gravitational center of the orbit, or Radial In, toward the gravitational center of the orbit. Both of these maneuvers work a little differently than I originally thought they might.

Radial Out

A Radial Out burn causes the rocket’s vector at the point of acceleration to rotate outward from the current orbit. As the rocket continues to accelerate in this direction, the point 90 degrees forward in the orbit increases in altitude faster than the point 90 degrees behind in the orbit decreases in altitude, leading to an elliptical orbit.

Radial In

Conversely, a Radial In burn causes the rocket’s vector at the point of acceleration to rotate inward from the current orbit. The point in the orbit 90 degrees behind increases in altitude faster than the point 90 degrees forward decreases in altitude.

Both of these maneuvers can be useful for making an orbit more or less elliptical. In particular, these maneuvers are useful for adjusting the periapsis of a hyperbolic trajectory (when passing by a celestial body that has not captured the rocket gravitationally), prior to reducing the orbital velocity to enter orbit. This will be discussed in more detail in the next post when we talk about travelling to and from other places.

Maneuvering Efficiently

Something that NASA often takes into account is Oberth effect (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oberth_effect), as well as angular momentum, and how this effects efficient rocket maneuvers. Now I don’t fully understand these effects, just the effect on the rocket which I will summarize at the end, but here is an attempt for a basic explanation. The Oberth effect states that the higher the velocity of the rocket, the more energy that is available in the propellant. So for the same amount of propellant burned, a faster moving rocket will have a larger change in speed. Conversely, it can be more efficient to lower an orbit from the highest point in the orbit, the apoapsis, because the velocity and correspondingly the angular moment is the lowest.

In a circular orbit, the speed is the same at the apoapsis as it is at the periapsis, there is no faster point to burn Prograde or Retrograde. On the other hand, when a rocket burns Prograde and raises the altitude of the opposite point of the orbit, the velocity at that opposite point slows down. While this seems counterintuitive that the rocket would end up travelling slower at the apoapsis after adding speed to the orbit, this is very similar to fighter pilots trading speed for altitude. Conversely, when burning Retrograde, as the altitude at the opposite point of the orbit reduces, the velocity at that point increases.

Once all of these factors are considered, some things can be realized about orbital maneuvering. Raising the orbit to intersect with a moon or transfer to interplanetary space is most efficient at the lowest possible altitude, where the rocket will be moving the fastest and take advantage of the Oberth effect. If you have a higher circular orbit, it can actually be more efficient to lower one half of the orbit, then burn Prograde at this low point in the orbit to raise the other half of the orbit to intersect with your target altitude. Lowering an orbit, such as returning to Kerbin or the Earth, is done most efficiently while at a high point in the orbit, again it can actually be more efficient to raise one half of the orbit, then lower the other half of the orbit once you reach this higher, and slower, point in the orbit.

Usually transitioning a circular orbit with a Hohmann or bi-impulse transfer is the most efficient, but due to these other effects, there are cases where a bi-elliptic transfer can actually be more efficient, where the rocket actually performs 3 separate burns. The idea is to start with a large acceleration #1 that produces an elliptical orbit, then a smaller burn at the apoapsis in this elliptical orbit #2 to bring the periapsis up to the desired altitude, and finally at this new periapsis #3 burn Retrograde to circularize the orbit. This method can be more efficient than a Hohmann transfer, but is typically much longer to circularize the orbit, making it good for some satellite applications.

The math of these transfers confuse me, so I generally stick to Hohmann transfers, not computing which is more efficient.

The most efficient time to change inclination, or perform a radial burn, is when the rocket is travelling the slowest, just like a retrograde burn, at the apoapsis of the orbit. Again, it can actually be more efficient to raise the apoapsis before performing an inclination change at the apoapsis. This is true of both directions of inclination changes or radial burns.

Long Burns

One final note about orbital maneuvering, these axes shift as we maneuver. Given an ideal impulse, an instantaneous acceleration, a maneuver could be set with a given point and direction. Since most rockets take time to accelerate, some rockets take a very long time, we have to design our maneuver for the entire burn, possibly changing our orientation from the start to the end of the burn. For example, burning in the Normal direction causes the plane of the orbit to rotate, changing the direction of both the vector of travel of the orbit, and the Normal direction (perpendicular to the plane of the orbit). One option is to compute a burn vector that will result in the impulse desired for the Normal maneuver over the full burn. While this works, I believe part of the burn ends up being wasted. Alternatively, the rocket can keep following the Normal vector as this vector shifts during the maneuver.

This covers the basic maneuvers possible while in orbit. In the next article we will talk about how to use these maneuvers to travel to some other place we want to reach.

Comments